Day to day we do not take into account the words we use, words we read, or words we hear. All this makes up language. There are roughly 6,500 languages in the world. Humans are the only species with a spoken language. But what of our cousins? In the following blog I will discuss the way non-human primates communicate, how we are able to communicate with them, and what makes the Homo sapiens so special as to have a spoken and written language.

Most non-human primates have a system of communication. To us it only sounds like, well, sounds, but to others in their species, they know exactly what they are saying; or feeling. The sounds chimpanzees make or when a baboon barks are being made to tell others in the group what they are feeling. They have sounds for happy, sad, angry, excited, but that is the extent to their “language,” to help others understand what they are feeling. I would say that was the only thing they can communicate, but we have to remember that most small non-human primates have predators, and as such, need to communicate extensively to keep safe. For example vervent monkeys (image below), they use different vocalizations to warn of different predators. The vocalizations for birds or pray, snakes, or leopards are different. With the snake-warning call they look at the nearby ground, with the birds of pray-warning call they look towards the sky, and with the leopard-warning call they quickly climb the trees. To those who hear them once, they all seem the same, but with attentive ears and hearing them call over and over again, it becomes clear which ones mean which predator. Other non-human primates that have this system include (images below) cottontop tamarins, Goeldi's monkeys, red colobus, and gibbons (there are also birds and non-primate mammals who use specific predator calls).

Most non-human primates have a system of communication. To us it only sounds like, well, sounds, but to others in their species, they know exactly what they are saying; or feeling. The sounds chimpanzees make or when a baboon barks are being made to tell others in the group what they are feeling. They have sounds for happy, sad, angry, excited, but that is the extent to their “language,” to help others understand what they are feeling. I would say that was the only thing they can communicate, but we have to remember that most small non-human primates have predators, and as such, need to communicate extensively to keep safe. For example vervent monkeys (image below), they use different vocalizations to warn of different predators. The vocalizations for birds or pray, snakes, or leopards are different. With the snake-warning call they look at the nearby ground, with the birds of pray-warning call they look towards the sky, and with the leopard-warning call they quickly climb the trees. To those who hear them once, they all seem the same, but with attentive ears and hearing them call over and over again, it becomes clear which ones mean which predator. Other non-human primates that have this system include (images below) cottontop tamarins, Goeldi's monkeys, red colobus, and gibbons (there are also birds and non-primate mammals who use specific predator calls).

So if we know how they communicate we should be able to communicate with them, correct? But what if they want to communicate with us? Before I go on any further I wanted to make something clear, the major reason for non-human primates is not because of the lack of intelligence (they are very intelligent), but because of something they lack. “The fact the apes can't speak...with the differences in anatomy of the vocal tract and language-related structures of the brain.” If they could speak, I am sure they would be seen as human as...humans. That said, there is a movement to get chimpanzee's to been seen as human, but I am getting off topic. Many apes throughout the years have found a way to communicate with us humans in ways we can clearly know what they mean. Before it was thought they could not speak of the future or past, only in terms of present events and present peoples. But that all changed with an infant chimpanzee named Washoe. In 1966 the project of teaching her sign language began, and within 3 years her “vocabulary” consisted of 132 signs. “She asked for goods and services, and she also asked questions about the world of objects and events around her.” And years later when they brought a young male chimpanzee named Louis, she deliberately began to teach him when the researchers were not.

In 1967 another chimpanzee, named Sara was “taught to recognize plastic chips as symbols for various objects.” What made this interesting is the chips did not look like the object she would ask for. For example, the chip for apple was not round or red. This was exciting because it showed that she could understand symbols for different objects. Something else happened in the late 1970's that was just as exciting. If you remember in my previous paragraph that non-human apes did not speak of past or future events or refer to those who were not present; but that all changed with a 2yo male orangutan named Chantek. He built up his sign language vocabulary to 140 signs, “which he sometimes used to refer to objects and people not present.” He would also combine signs to make more clear what he was speaking of, he was the first to do this, but not the last. In the early 1970's a gorilla was born, a gorilla the world now knows as Koko. This magnificent gorilla does not have a vocabulary of 140, or 500, not even 1000; her vocabulary is more than 1000, and to add to that, she can also understand more than 2000 words spoken in English. As I said, just like Chantek, she has made very clever signs for things she wants. For example the sign for “scratch” and “comb,” she was asking for a brush (video below), or with the sign for “eye” and “hat” she means “mask.”

In 1967 another chimpanzee, named Sara was “taught to recognize plastic chips as symbols for various objects.” What made this interesting is the chips did not look like the object she would ask for. For example, the chip for apple was not round or red. This was exciting because it showed that she could understand symbols for different objects. Something else happened in the late 1970's that was just as exciting. If you remember in my previous paragraph that non-human apes did not speak of past or future events or refer to those who were not present; but that all changed with a 2yo male orangutan named Chantek. He built up his sign language vocabulary to 140 signs, “which he sometimes used to refer to objects and people not present.” He would also combine signs to make more clear what he was speaking of, he was the first to do this, but not the last. In the early 1970's a gorilla was born, a gorilla the world now knows as Koko. This magnificent gorilla does not have a vocabulary of 140, or 500, not even 1000; her vocabulary is more than 1000, and to add to that, she can also understand more than 2000 words spoken in English. As I said, just like Chantek, she has made very clever signs for things she wants. For example the sign for “scratch” and “comb,” she was asking for a brush (video below), or with the sign for “eye” and “hat” she means “mask.”

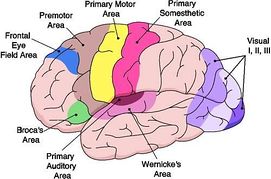

With all we have had to do to communicate with non-human primates, why is that we are able to communicate with other humans? Why do we have something called “language?” For the answer to that we have to look at the brain. Some argue that our language capabilities began 10,000 – 30, 000ya, others think it was earlier with the appearance of Homo (2mya). “In most people, language function is located in the left hemisphere...In particular two regions, Broca's area in the left frontal lobe and Wernicke's area in the left temporal lobe are directly involved in the production and perception, respectively, of spoken language (image below).” Broca's area is located near the motor cortex, right next to the area that controls the face, lips, larynx, and tongue. The Wernicke's area involved in the perception of sound. If a lesion in Wernicke's area is damaged, it does not impair hearing, but rather the comprehension of language. I have gone one about these two areas of the brain as if only humans have it, but that is not true. In examined chimpanzee, gorilla, and bonobo brains they have a larger Broca's area on their left side. But, that said, it is the same area that harbours the motor aspects of gestural language in humans; “speech production in humans was present, at least in a incipient degree, in the last common ancestor of humans and the African great apes.” In short, the shared cognition abilities of primates (especially apes), lead to some symbolic capabilities, which lead to the increased communication abilities and development of symbolic thinking (which was a huge and important step for both neurological reorganization and anatomical modifications of vocal tract), and all this lead to where we are now, a world full of languages; human languages.

Please feel free to comment on what you thought of the blog, or other physical anthropological subjects you would like me to cover.

Please feel free to comment on what you thought of the blog, or other physical anthropological subjects you would like me to cover.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed