Genetic drift is an evolutionary change in which it “occurs because the population is small.” How small is “small?” Did this happen and can it happen again? Is genetic drift good? But really, was IS genetic drift? In the following blog I will address these questions, and hopefully answer all questions you have about this topic.

So, what is genetic drift. I know I gave a definition in the first paragraph, but it was a very vague definition that would only make sense to those who already know what genetic drift is. It is a random factor in evolution which means it has ties in mutation. When an allele, which I mentioned in an earlier blog (http://anthropologicalconcepts.weebly.com/blog/you-have-your-mothers-eyes) is rare in a population, a small population (a few hundred), it may not be able to pass on to the off spring because if the allele is rare, that means it is recessive. This may seem like a small thing, but this means the “genetic variability in this population has been reduced.” And in the unlikeliness of that allele being passed on, that trait dies in that population.

That said, it answers the “is genetic drift good” question; no it is not. There is a particular type of genetic drift that can lead to another more drastic type. The particular type is called “founder effect,” in which “allele frequencies are altered in small populations that re taken from, or are remnants of, larger populations.” This type did occur, and still does occur in modern human (and nonhuman) populations. Founder effect can happen when a small party breaks off a bigger one and establishes themselves elsewhere. When they choose to procreate they will most likely choose one of their party. So over time the genes of the original founders will be the only one's in their expanded group. “In such a case, an allele that was rare in the founders' parent population but, just by chance, was carried by even one of the founders can eventually become common that group's descendants.”

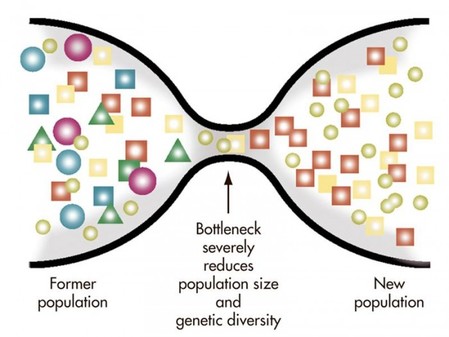

Now, as I mentioned in the previous paragraph, there is a more drastic type of founder effect; this type is known by the term “genetic bottleneck.” The reason I call this type “drastic,” is because the effects can be extremely damaging to a species. While a small population (“with considerable genetic variability”) has a chance to get some of the same variability, an original population with the same considerable genetic variability, when a small group leave to colonize another area is where the bottleneck occurs (image below). When the population size is restored, there will be less of the genetic variability as the original population. Cheetahs for example, genetically they are an “extremely uniform species.” Biologists believe in the past there was a huge decline in numbers, and for reasons that are left up to skepticism, the male cheetah produces a “high percentage of defective sperm as compared to other cat species.” So this decreased reproductive potential, and other factors (hunting by humans for example), but the cheetah in very dangerous waters. On the subject of species, we humans are also very uniform genetically as well. Reason being a good amount of our evolution (the last 4 – 5 million years), we most likely lived in small groups, and in doing so the “drift would have had a significant impact.”

So, what is genetic drift. I know I gave a definition in the first paragraph, but it was a very vague definition that would only make sense to those who already know what genetic drift is. It is a random factor in evolution which means it has ties in mutation. When an allele, which I mentioned in an earlier blog (http://anthropologicalconcepts.weebly.com/blog/you-have-your-mothers-eyes) is rare in a population, a small population (a few hundred), it may not be able to pass on to the off spring because if the allele is rare, that means it is recessive. This may seem like a small thing, but this means the “genetic variability in this population has been reduced.” And in the unlikeliness of that allele being passed on, that trait dies in that population.

That said, it answers the “is genetic drift good” question; no it is not. There is a particular type of genetic drift that can lead to another more drastic type. The particular type is called “founder effect,” in which “allele frequencies are altered in small populations that re taken from, or are remnants of, larger populations.” This type did occur, and still does occur in modern human (and nonhuman) populations. Founder effect can happen when a small party breaks off a bigger one and establishes themselves elsewhere. When they choose to procreate they will most likely choose one of their party. So over time the genes of the original founders will be the only one's in their expanded group. “In such a case, an allele that was rare in the founders' parent population but, just by chance, was carried by even one of the founders can eventually become common that group's descendants.”

Now, as I mentioned in the previous paragraph, there is a more drastic type of founder effect; this type is known by the term “genetic bottleneck.” The reason I call this type “drastic,” is because the effects can be extremely damaging to a species. While a small population (“with considerable genetic variability”) has a chance to get some of the same variability, an original population with the same considerable genetic variability, when a small group leave to colonize another area is where the bottleneck occurs (image below). When the population size is restored, there will be less of the genetic variability as the original population. Cheetahs for example, genetically they are an “extremely uniform species.” Biologists believe in the past there was a huge decline in numbers, and for reasons that are left up to skepticism, the male cheetah produces a “high percentage of defective sperm as compared to other cat species.” So this decreased reproductive potential, and other factors (hunting by humans for example), but the cheetah in very dangerous waters. On the subject of species, we humans are also very uniform genetically as well. Reason being a good amount of our evolution (the last 4 – 5 million years), we most likely lived in small groups, and in doing so the “drift would have had a significant impact.”

As I said before, genetic drift is not a good thing, mostly because the retention of a disease or condition in a population. There are some that can happen to anyone (cystic fibrosis, a variety of Tay-Sachs, sickle – cell anemia, but the last one is actually an advantage, I will explain why later), but most common within small populations. For example there is a recessive but fatal condition called Amish microcephaly, in which a mutation causes abnormally small brains and heads of fetuses. Unlike my previous statement some can happen to “anyone,” this specific condition is only found within the Old Order Amish community of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, United States. Even though this is recessive it occur in approximately 1 in 500 births. Now I mentioned that sickle – cell anemia is an advantage, reason being those with this benign condition are more likely to be a survivor of malaria (“an intermittent and remittent fever caused by a protozoan parasite that invades the red blood cells.”) And the reason why those with sickle – cell, which provides 60% protection against overall mortality, is because, it is suggested, the hemoglobin (the protein responsible for transporting oxygen in the blood) gets in the way of the parasite and in doing so the infected results with a low percentage of infected red blood cells.

After this blog, I hope I have opened your minds to go beyond your neighbourhood or ethnic group to put a stop to the damage genetic drift can cause (and has caused thanks to our evolutionary ancestors). Please feel free to comment on what you thought of the blog, or other physical anthropological subjects you would like me to cover.

After this blog, I hope I have opened your minds to go beyond your neighbourhood or ethnic group to put a stop to the damage genetic drift can cause (and has caused thanks to our evolutionary ancestors). Please feel free to comment on what you thought of the blog, or other physical anthropological subjects you would like me to cover.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed